Throughout history, attempts have been made to capture the essence of an experience and distil it in some form to make it available for us to enjoy and analyze. Through the direct experience of theatre, music. and paintings, people have been able to perceive both the real and imaginary expressions of other worlds, other times. new ideas, and new perspectives on old ideas. Computers and virtual reality aren’t the first tools to change the way people absorb. debate, and relate to knowledge.

The Greeks of the 4th and 5th centuries B.C. used theatre, public debate. and storytellers as tools for thought. They were discovering and inventing a new world order of science, art, and society. The theatre was a way to engage and focus the public’s attention, to take them to the distant shores of Troy or the halls of Olympus while simultaneously involving them in the great philosophical debates, acted out in the emotions and decisions of dramatized events. Much like some TV shows of today.

As the entertainment industry begins to recognize the enormous potential of VR and the Metaverse there will probably be a proliferation of commercial gimmicky you will have to endure along the way. It might take a few years for most industries to fully integrate their marketing into VR, but it will happen given enough time. After all, it took them over 17 years before the first TV advert was shown!

The Birth of Television

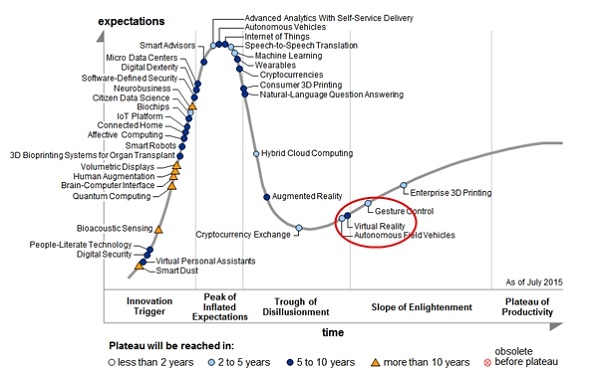

It’s interesting to compare the public introduction of television in 1941 with the introduction of VR. Here was a technology fascinating to view, though limited in content and image quality. Crowds formed wherever it was initially demonstrated. Ideas abounded about possible applications. but predictions fell far short of actual uses. Sound familiar? Welcome to what is called The Slope of Enlightenment.

Television provided a mass distribution system bringing much of the impact of movies into everyone’s home. No longer did people have to go to the theatre—now the theatre was delivered to the home. Technology like VCRs and DVD’s (and now steaming) drew viewers away from the movies. In addition, television could do what movies could never do: it could put viewers on the scene live! It introduced the concept of telepresence, the sense of being there through the eyes of the camera.

While the 1991 war in the Persian Gulf dramatizes this effect. it was the Kennedy assassination that first truly drove this point home as the entire nation participated in the disaster and mourning.

Over the years, television’s potential for escapism and distortion of the nation’s moral fabric has been debated; much as today. similar debates swirl over the role of virtual reality.

Some adults are not comfortable with the role television plays in our lives. Even now we are still trying to understand the impact and influence of television and indeed the internet on all our lives. Using television and film to create a sense of realism had one important drawback; the audience felt as if they were watching the action through a large window or frame. All the drama was out there beyond the window: nothing ventured inside the theatre. The audience was isolated from directly experiencing the events shown on the screen. 3-D movies were marginally successful at breaking through this barrier and bringing the action inside, but they didn’t succeed because they were too gimmicky.

To allow a more direct experience, a larger image would have to be captured and displayed so that it would fill the audience’s entire field of view. Our eyes can see about 180 degrees horizontally and about 150 degrees vertically. Depending on where someone sits in a theatre, a 35mm film screen could be as small as 50 degrees horizontally and 38 degrees vertically. This is about 5% of our visual field. Television is much worse. Various approaches were tried to expand the view and in the early 1950s, Fred Waller convinced producer Mike Todd to invest $10 million in a new process called Cinerama.

Three synchronized 35mm film cameras recorded each scene from slightly different views. In the theater, three projectors displayed the separate images onto a specially built screen that curved around the audience and provided almost an entire 180 degrees of horizontal view. The image was now three times as wide and nearly twice as tall (it used a taller film format). With six times the visual image and six-track stereophonic sound, it dramatically increased the perception of experiencing reality rather than looking through a window.

Narrative movies such as How the West was Won (1962) and The Wonderful World of the Brother’s Grimm (1962) were shot using this process. Though popular, the cost of outfitting theatres and difficulties in synchronizing and producing films using three cameras instead of one proved too formidable. How the West was Won, for example, required the services of three directors (John Ford, Henry Hathaway, and George Marshall) and four cinematographers and cost over $14 million to shoot (which is $128 million in today’s money). At its height of popularity, only one hundred theatres in the world were equipped to show Cinerama films. After 1963, movies were no longer produced using the Cinerama format, but it’s credited with bringing audiences back to cinemas in numbers unseen since 1946. It proved that audiences would respond to experiences that had a greater sense of presence-of being there.”

Hollywood, threatened by the popularity of television in 1950, recognized the value of the wide-screen experience and began searching for other solutions. In 1953, simpler processes such as Cinemascope and later 70mm Panavision were developed for the widescreen and are still in use today (in addition to Omnimax (often seen in I-Max cinemas), which is the ultimate wide-screen experience, with almost a total field of view horizontally and vertically). People were willing to pay for the experience of being immersed in a movie. Fortunately, Morton Heilig (a young cinematographer from Hollywood), had a chance to experience Cinerama in the early 1950s prior to its demise.

Morton Heilig’s Sensorama

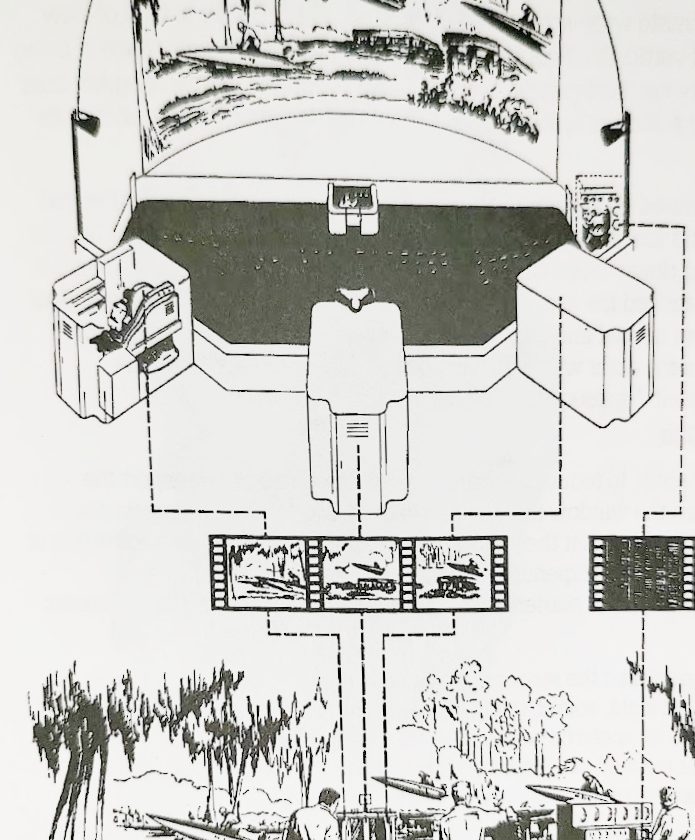

Realizing its potential to reduce the barrier of the screen and to transport the audience through the window into the movie itself, Morton Heilig proposed a radical idea. He decided that the logical future of the film industry would be that of supplying highly realistic experiences to large audiences. His goal was the complete elimination of all barriers that kept people from accepting the cinematic illusion. Methodically, he studied the sensory signals used to distinguish illusion from reality. He isolated sight, sound, touch, and smell as the primary senses needed for stimulation. Next, he analyzed what current technology could provide for sensory stimulation. This resulted in a clear understanding of the pieces missing to complete his concept of the “experience theatre.”

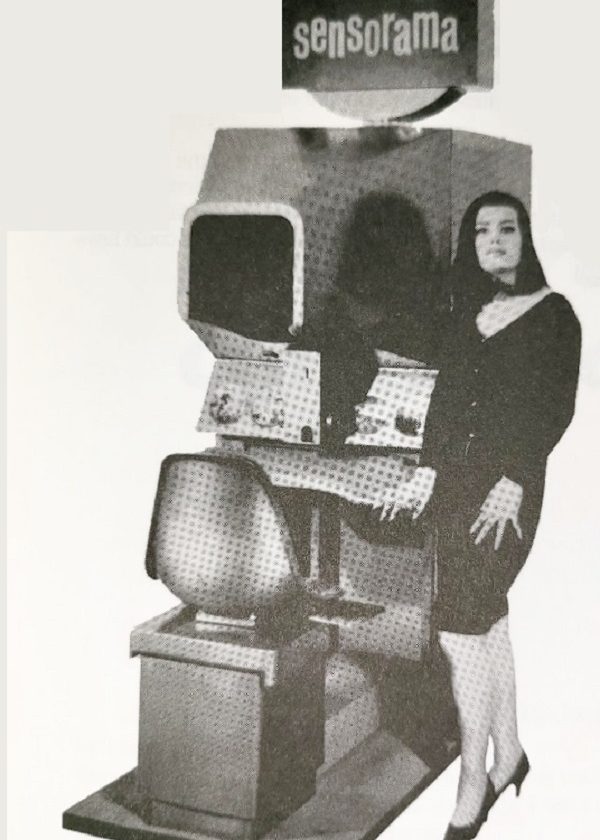

With little more than simple faith in his ideas, Heilig attempted to revolutionize Hollywood. Unfortunately, Hollywood wasn’t listening. Despite repeated attempts to communicate his call to revolution, he didn’t find any support in the film industry. After moving to Mexico in 1954 and receiving financial backing for some initial research, his backer was killed in an accident, forcing Heilig to return to New York. By 1960 he and a partner created a personal version of the experience theatre as a way to demonstrate his concepts. Similar to an arcade machine, it was called Sensorama!

It was outfitted with handlebars, a binocular-like viewing device, a vibrating seat, and small vents that could blow air when commanded. In addition, stereophonic speakers were mounted near the ears, and close to the nose, a device for generating odours specific to the events viewed stereoscopically on film. One of the recorded “experiences” was a motorcycle ride through Brooklyn. The seat vibrated, you felt the wind against your face, and you even smelled different odours as you passed along the street-a full sensory experience that hasn’t been duplicated in full even with the latest VR experiences.

Of course, you couldn’t direct the motorcycle to turn down your favourite street because it wasn’t interactive, but you received a very direct experience as a passive observer. This was the logical evolution in the search for realistic, immersive experiences, but the film industry didn’t realize it. They also had problems with the economics of Heilig’s ideas. Films absorb very high production values that either must be amortized over time or across a mass market to get the necessary return on investment. Movies are very expensive to produce but relatively easy to reproduce and distribute. And they can be experienced by large groups so that costs can be spread out over repeated viewings by large audiences. Heilig’s stand-alone ride would require thousands of “rides” to pay back its cost, or otherwise, the cost of each ride would be prohibitively expensive.

Of course, Hollywood would also miss the significance of the video-game craze of the 1980s and the multi-billion dollar revenues it generated. Video games provided personal entertainment through dedicated hardware. The film industry is one of few that is successful despite spending an insignificant amount on research and development on new technologies. After a few more unsuccessful attempts at marketing Sensorama and the development of another prototype for a different backer, Heilig had to accept the inability of the industry to recognize Sensorama’s potential. Finally, the first truly virtual reality machine was covered up and rolled away to storage, never to be seen again.