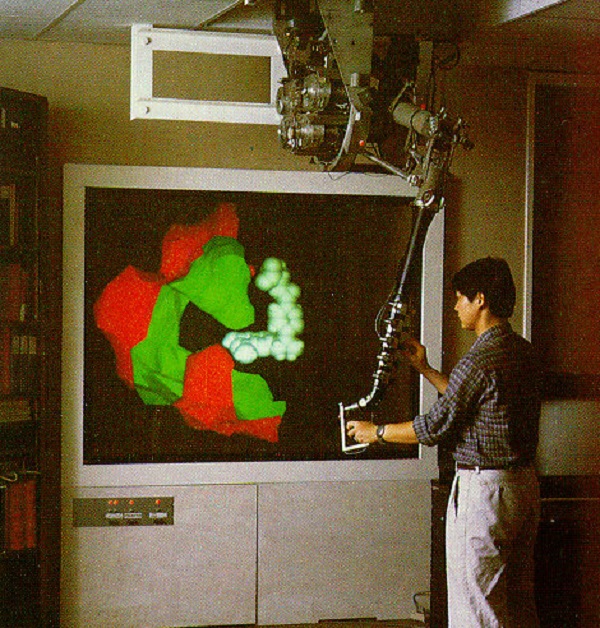

It wasn’t until 1986 that computing power had increased sufficiently to justify dusting off the GROPE system and having another go at the problem. A simulation of a drug with over 1500 atoms and a protein of 21 atoms was modelled on the new GROPE-III system. Wearing polarized eyeglasses, the chemist viewed a stereoscopic image of the molecules. This gave her a sense of depth as she tried to manipulate the molecule using the ARM. Even with one hundred times the computing power of the original GROPE-II, the simulation was so complex that it took a third of a second to render each image (3 fps). This resulted in jerky, noncontinuous motion. For realistic modelling, closer to twenty frames per second would be required.

Despite the limited performance, Brooks researchers learned that the system could still be effective for studying docking problems. By reducing the complexity of the model they increased the frame rate and managed to make something they could finally work with. Now docking the model felt like holding a six-inch magnet in your hand and moving it closer to an identical magnet in a fixed place. identically charged surfaces attracted, pulling your hand closer. You could feel the force field surrounding the molecules.

But chemists weren’t the only ones to have their minds amplified at UNC. Architects were also among the chosen few. For centuries, they had struggled with communicating their vision to those around them. Using scale models and perspective drawings helped, but were inflexible. If the customer wanted changes, the model would have to be rebuilt or the drawing redone. This was both expensive and time-consuming. Architects and their clients would benefit tremendously if they had a tool that allowed them to visit the design and walk around it before it was even constructed.

In the mid-’80s, UNC decided to construct a new multimillion-dollar building called Sitterson Hall. This was to be the new home of Brooks’ group of researchers. As they would be spending many hours within its walls, the researchers were very interested in the building’s design. They decided to create a simulation of the structure using the technology they had spent years developing

With blueprints as a guide, they modelled the structure in 3-D using the computer instead of building a scale model in foam or wood. Using a powerful graphics computer, they were able to position the viewpoint anywhere in the model and quickly render the scene. By controlling the direction and speed of the viewpoint, they were able to generate a consecutive series of images of the interior or exterior.

It was like watching a film that someone had shot while walking down a hallway of the yet-to-be constructed building. But, unlike a movie, you could interactively decide which hallway or room to explore. No limits were imposed on where you might look and at what viewpoint. Taking this level of immersion a step further, they hooked up a treadmill and movable handlebars to the computer. This allowed you to physically walk down hallways while steering yourself by turning the handlebars. The image of the hallway was projected on a screen in front of you, although in later demonstrations they used a simple head-mounted device based on LCD screens.

The experience was realistic enough that they determined that a certain partition in the lobby caused a cramped feeling. Once the architects experienced the simulation, they agreed and the partition was moved.

This computer simulation provided valuable knowledge that was then used to improve the environment. Architects could now directly experience their design and improve upon it based on what they learned from their virtual explorations. Clients exposed to the simulation could provide valuable feedback long before the first concrete was poured. Architecture, perhaps more than any other field, was poised to reap the benefits of virtual reality and the same can still be said today, especially with 360 cameras allowing you to view a house from anywhere in the world.

So now the processing power was there all that was needed was a way to put people into these virtual simulations. The VR headset was about to become a very real thing and it was all thanks to NASA.